Book Report: The Making Of Star Trek

Or, How Game Development Is Far Closer To Other Media Than You Think

I’ve had the great fortune in this life of not only being associated with several people in film, TV, print and radio but also as mentioned briefly in the last post I worked in the sphere for roughly 10 years. Most of my duties were in post production, which is typically the final stage of any piece of media. This meant I was witness to the end result of various writers, camera operators, producers, set designers, sound engineers and various other roles, while my own tasks involved translating and editing scripts, or lending my voice for the purposes of dubbing in the sound booth.

It is from this perspective that I approach The Making Of Star Trek by Stephen E. Whitfield. The book was originally published in 1968, shortly after the second season of the original Star Trek show wrapped up, and came to me via recommendation of my coworker. Given my experience in game dev on top of “traditional” media, I was greatly amused - but not in the least surprised - by Whitfield’s introduction.

Though I do not consider myself a Star Trek fan, it is an excellent postmortem filled with minute specifics on every aspect of the show’s production.

A COUPLE OF THINGS TO NOTE

Before we continue:

It’s quaint to think of it now but Star Trek was at the time of its creation a precarious endeavor. Using an inflation calculator to put it in today’s money, each episode of the first season would have cost somewhere between one to two million US dollars to make, and throughout the book the topic of resources is a constant problem - but funds weren’t just the only thing. Creator Gene Roddenberry by his own admission wanted the show to be fundamentally optimistic, tackling heavy topics like societal intolerance at a time when the civil rights movement was in full swing. Network executives balked at it, with both MGM and CBS turning down the pitch after months of Roddenberry waiting on them for a response. Desilu Studios, the ones responsible for producing the first season, were gambling on a totally new intellectual property and they weren’t even sure people would tune in to watch. So much was going against pretty much every aspect of the show that it’s a miracle it even got out the door, let alone received as well as it did. Sound familiar?

Conversely, Star Trek was made in the 60s and both it and the book are a product of the times. The purpose of this post isn’t to tackle patriarchy’s myriad crimes - but it does need to be mentioned that the show was rife with misogyny (put “sexism in Star Trek” into a search engine to get numerous articles on the matter, particularly specific people key to the series like D.C. Fontana and Nichelle Nichols) and this is at times reflected in Whitfield’s text. At the same time, Whitfield at least acknowledges the various women involved - for instance from the introduction earlier:

…and this sort of acknowledgment of just how much work everyone was doing repeats throughout the book, but it tends to skew towards the male figures much more than any of the women involved. Again, sound familiar?

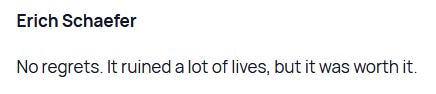

These two topics are not what I wish to dwell on, in part because I’m not capable of tackling them and mainly there are far better commentators who can more aptly critique Star Trek in the context of civil rights, feminism, labor movements, and so on. However, even over fifty years ago creative figures still had to contend with convincing purse string-holding risk-averse executives to part with their money, and people were still getting swept up in a heady workaholic atmosphere in pursuit of the new only to burnout in the process - and I think it’s hard to argue that either dynamic has changed much in the years since in other creative industries. For instance, at the very end of the excellent oral history of Diablo II put together by Kat Bailey (originally posted in 2015 on usgamer.net), we read:

And compare that to what Roddenberry says on page 379 of Whitfield’s book.

So I’m not going to judge by contemporary standards either the book or the show that came out decades before I was born - though I will do the bare minimum of pointing these things out because to various extents we’re still dealing with the same problems.

What I do want is to highlight some of the things revealed in the book that I think anyone in any creative endeavor ought to be doing. Just because they did these things half a century ago doesn’t mean they’re useless or outdated.

KEEPING TRACK OF MONEY

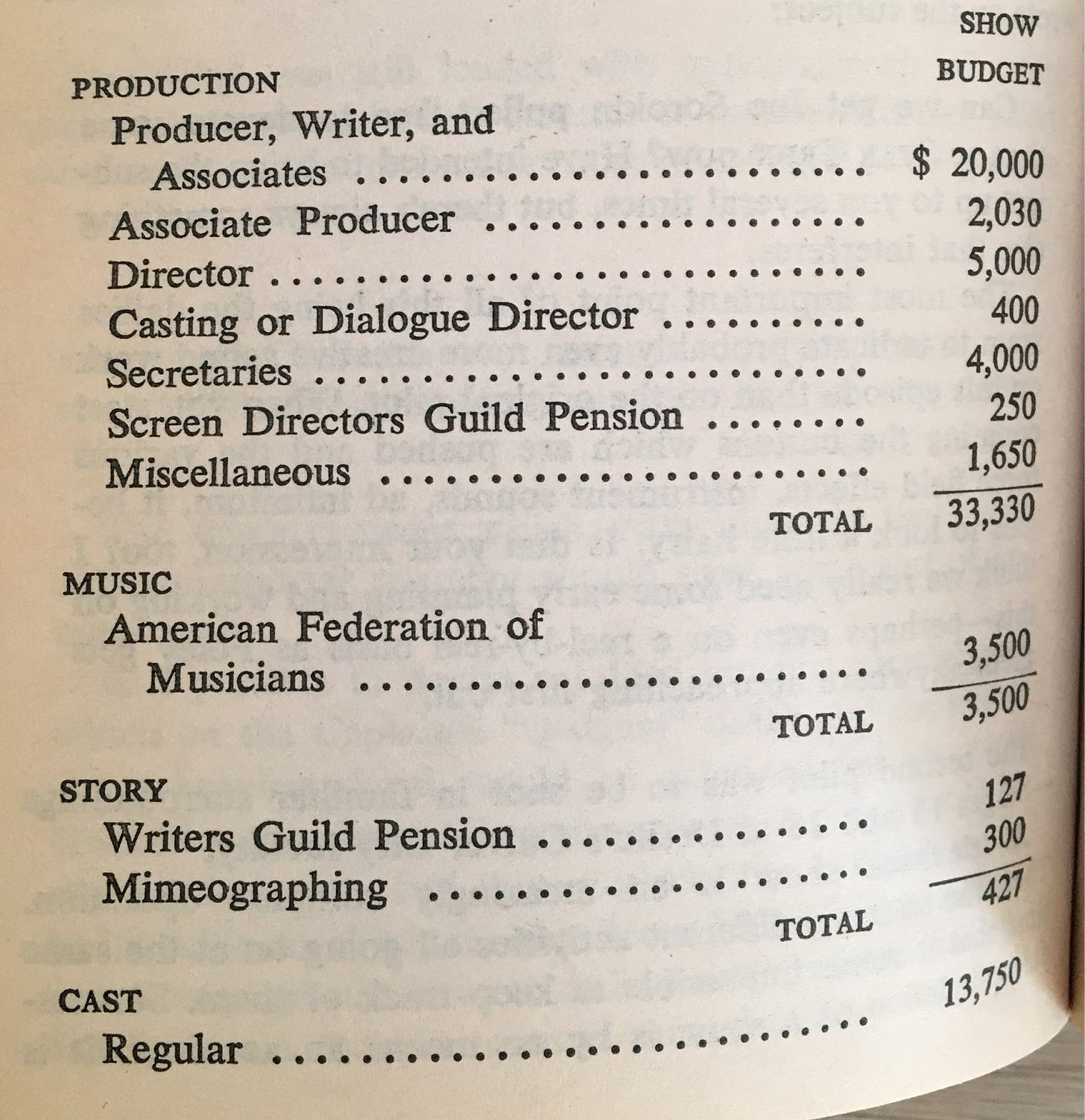

On page 140 we are treated to a detailed breakdown of the cost of the second pilot for Star Trek (the first pilot flopped and another was requested following feedback, which is almost unheard of). To put them into 2023 sums, multiply each line item by at least ten to get a rough equivalent.

Money is a frequently difficult subject to bring up in most work environments. By not only estimating a budget and breaking it down ahead of time, but also making it known to every department helps do two things:

Forestalls any wild ideas creative leads might have

Reinforces what is actually important and urgent

In the context of the book, Star Trek was an untested format and had time constraints, so it was vital that they kept to a budget. Knowing what that sum was in advance of production was also important to the stakeholders - because the studio needed to know what amount of risk they’re taking on - as well as to the cast and crew who are the ones spending that money. Even if they were to go over budget (spoilers: they did), they at least had a plan on what to do with that money from the outset.

The relevance this has for game development is to look at any competent pitch deck for a video game project that has successfully sought funds. The ones that are much more likely to get funded are those that know what amount of money they need and for what, and within what time frame they can deliver a return on that investment.

SCHEDULES & CALL SHEETS

From about page 146 onwards we are treated to a sample shooting schedule and a call sheet. One of the commonalities of both game development and on-set production is that it’s very rare for the order of things that appear in the end result to be created in the same order during production. Instead, scenes will be shot in a way that makes the most sense to everyone and everything involved. For example if multiple scenes in an episode involve discussions between characters in a corridor set, the shooting schedule dictates that all the corridor scenes be shot the same day. The reason you do this is largely due to the logistics of swapping sets and props around in (and out of) a sound stage, to say nothing of the people involved, so the shooting schedule and the show’s script will not follow the same order. The aim is efficiency, because if you couldn’t tell from the previous images, on-set production is ludicrously expensive.

The call sheet is similar, albeit aimed more at cast and crew. A call sheet will, among other things, tell you who is turning up on set that day, what scenes they’ll be in, but more importantly when they need to be there. As can be seen, Leonard Nimoy had to be present earlier than everyone else due to the application of Spock’s ear prosthetics, and due to the workload on set also needed to be specially catered for along with Shatner.

That furnished breakfast isn’t some sort of prima donna behavior on either Shatner or Nimoy’s part - they both led the show and as such had to spend a lot of time on set. If they had to also deal with making themselves breakfast, that’s further time wasted that could otherwise have been spent on the job at hand (again, please recall Odenkirk’s remarks referenced in the previous post).

The clearest parallel I can see to game development is things like exhibiting at events like PAX, where it is counterproductive to have everyone on the team manning the booth at the same time, as well as basic things like making sure everyone is fed and watered throughout the event.

CAMARADERIE & TRUST

Throughout the Making Of Star Trek we are treated to numerous memos exchanged between various staff members, usually Bob Justman and Gene Rodenberry. If the text were divorced from the book and the language wasn’t dated in places, these things end up reading exactly like a company BBS or the comments section of a ticket system. For instance page 387 has the following.

It’s entirely in jest, but note Whitfield’s comment after it about “the light-hearted atmosphere that can prevail, even in the midst of turmoil and chaos”. What immediately follows that in the text is a protracted exchange of memos between multiple staff teasing one another over the topic of office furniture. It’s all farce, of course, but is indicative of the relationship everyone had with one another during production.

My takeaway from this is there was an extremely strong bond of trust between everyone involved, even keeping in mind Gene Roddenberry’s (probably) overbearing desire to be involved in as many aspects of the production as possible, but he at least realized that he couldn’t do every single thing - the show was a team effort, and as easy as it is to point out, so is game development. If you’ve instead got a fractious team to contest with, production is going to be much worse.

IN CONCLUSION

Many more lessons can be drawn from The Making Of Star Trek for other disciplines in game dev, such as level and narrative designers and particularly marketing, but the book is so rich in its details that it’s frankly better if you quit reading this and go out and get a copy for yourself - even if you don’t particularly like Star Trek.

Personally, The Making Of Star Trek is one of those rare books that ultimately gives me a new lens through which to examine and better understand some of my favorite media. For instance, I now appreciate much more the minutiae seen and heard in the first 45 seconds of this scene from Hail Caesar by the Coen Brothers, which is set roughly ten years before Star Trek would have begun production.

Copies of The Making Of Star Trek can be found in the usual places online, as well borrowed from the Internet Archive, but I recommend purchasing a physical copy.

This is a really cool insight! I'm a huge fan of OG Trek, even the most problematic episodes have really cool things for me to appreciate in them. Very cool to know how the teams managed to function despite Rodenberry's unrelenting vision, I'd always pictured him a difficult person to work for. The makeup specifically is so incredible, it would be really cool to see the people who did it break things down, even if they aren't able to get into the more problematic aspects of the makeup in certain episodes.